Pumps: Missing in Climate Action?

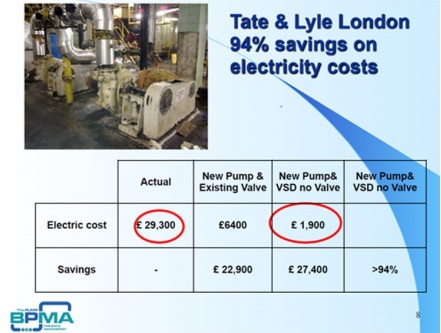

Figure 1 shows the results of an energy audit carried out in 2011 for Tate & Lyle London. (Image source: BPMA)

The UK Government has announced a ten-point plan for a green industrial revolution covering clean energy, transport, nature, and innovative technologies. The blueprint is intended to allow the UK to wipe out its contribution to climate change by 2050. However, the contribution of pumps to global warming is not being addressed in this ambitious plan, despite the UK’s past commitment to tackle the issue. This is a serious oversight, given the high energy use of pumps and their critical role in maintaining our industrial base and standard of living.

The policy challenge

Larger industrial pump users have been required to carry out audits of energy use and introduce improvements under the UK’s Energy Saving Opportunity Scheme (ESOS), since 2015. However, some have taken advantage of a loophole allowing them to opt out of this requirement, if they complied with the ISO 50001 standard aimed at energy management. This has meant they have avoided identifying inefficient pumping systems and subsequently making them more efficient, which would significantly cut their energy use and help the environment. The latest revision of ISO50001 has closed this loophole but weak market surveillance and low penalties mean that action in this important area remains stalled. A ‘carrot and stick’ approach is needed. Fines should be significantly increased to make sure that ‘bad-players’ can no longer afford to ignore the problem. In addition, appropriate government support should be provided to make the financial case for change more attractive and help the drive towards Net Zero.

The missing 11th point

The government’s ten-point plan towards a Green Industrial Revolution are diverse, and in some cases the anticipated savings are some time away. They range from supporting wind power, nuclear energy and zero emission vehicles, to encouraging green buildings and transport, including advanced aviation. There is a praiseworthy emphasis on securing quality future jobs in these ‘new horizon’ sectors as well as helping the environment. However, there is a notable lack of attention to some existing core sectors of UK industry that also have a bright future, but which need to invest in energy savings. We believe the huge savings to be realised by improving the energy efficiency of our pumps and pumping systems should become the 11th point in the Government’s plan.

To take a few examples, the anticipated savings in million tonnes of CO2 equivalent in the 12-year period up to 2032 from greening public transport, the shift to zero emissions vehicles, and green ships amounts to 7 MtCO2e. However, if we extrapolate over the period from 2015 to 2032 the hoped-for annual energy savings of 7TWh, produced by greening pumps, would have amounted to 119 TWh or around 60 MtC02e. This is on a much greater scale than the CO2 savings of the three elements of the government’s 10-point plan previously mentioned.

In fact, it is almost three times the expected longer-term savings – between 2023 and 2030 - from advancing wind power, which according to the government figures is expected to attract around £20 billion of private investment by 2030 and amounts to around 5% of 2018 UK emissions.

How did pumps get missed?

To move a liquid from A to B a pump is required. Therefore, industrial and domestic applications are a vital component of modern living. Given their importance, it is not surprising that they are big energy users. The question has always been, can better engineering improve matters and deliver significant energy savings that can help us on the road to net zero?

Many pumping systems operate inefficiently, however as the pump is ‘doing what it is supposed to’ there is no focus or requirement to look at the energy efficiency of the pump or the system in which it operates.

A lot of the installed base of pumps is older technology and inherently more energy hungry, and which invariably have been ‘over specified’ because engineers and plant managers have wanted to ensure that if they need ‘more muscle’ for their processes, there is extra capacity available. Older style pumps were therefore typically over-sized and as such seldom work at their optimum efficiency. Newer pumps are designed to operate efficiently at variable speeds, so they have the built-in flexibility demanded without the energy “penalty”.

The Tate & Lyle case shows a 94% saving in electricity costs (£29,300 annually) by replacing the original single speed pump and reduction valve for a variable speed pump.

Since a proper energy efficiency policy needs to tackle the issue of the bigger users, the UK Government established the ESOS (Energy Saving Opportunity Scheme) to implement Article 8 (4 to 6) of the EU’s Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EU).

A company needs to comply with ESOS if the organisation has over 250 members of staff; or a turnover of over £44.1m or an annual balance sheet of over £37.9m; or is part of a larger organisation which falls into any of the above. Non-compliant companies face fines of up to £90,000.

Companies who fall within the scope of ESOS are required to undertake an energy audit conducted or overseen by an approved ESOS Lead Assessor. The pump manufacturing and repair industry reacted positively to this development by investing heavily in training qualified auditors and was fully ready to support the policy. However, there was opposition from some major industrial companies who saw this change to better, more reliable, and up-to-date technology in terms of increased cost, rather than as an opportunity for savings. As a result of their lobbying, they succeeded in getting agreement that organisations fully covered by ISO 50001, which is aimed at energy management, did not need to have a separate ESOS audit.

Under UK law, ESOS or ISO 50001 audits must be conducted every four years. The first deadline was 5 December 2015, the second was 5 December 2019 and the next deadline will be 5 December 2023. So, in principle, the larger companies covered by this energy audit requirement should have been busy since 2015, upgrading their pumps to a green standard, as indicated by the audits. However, those who opted for ISO 50001 saw a convenient loophole since, unlike the ESOS audits, ISO 50001 (2012) did not require the audit recommendations to be enacted upon.

Despite the challenges of Covid-19, the fate of the planet has been coming into increasing prominence. This is demonstrated by the UK Government’s commitment to its 10-point plan for a Green Industrial Revolution. It is also reflected in the updated version of ISO 50001 (2018). Within sections 9 and 10 of the 2018 version the standard now stipulates that energy savings identified must be achieved or certification will be withdrawn. This means that, finally, all companies covered by the legislation must have energy audits and that the audit recommendations should be carried out.

What action is needed?

Perhaps it may seem that the problem is solved. The big industrial users of pumps have been given their marching orders and the government can concentrate on the new horizon industries in the 10-point plan, putting the potential savings just identified into the carbon bank.

Unfortunately, there continues to be strong resistance among some sectors to undertaking meaningful pump audits. Most probably, the debate doesn’t even reach the boardroom, and even where there is a solid investment case, nothing happens.

The remedies are two-fold. Market surveillance in the UK, despite the convenient assumption that we somehow have the ‘gold standard’ when it comes to following rules, is lamentably absent in this area. Even if a company is identified as being in breach of ESOS a penalty of £90,000 is not even a slap on the wrist for a big business.

Decisive action is needed to tighten enforcement. Introducing meaningful penalties, perhaps based on a proportion of company turnover, should be considered. In addition, there must be the political will to resist what is often misinformed pressure from big industry. On the other hand, while many of the cases for upgrading pumps will be clear-cut, financial assistance to encourage modernisation should also be examined.

Not all industries can be “new horizon”, so surely the 11th point in the UK Government’s plan must be to ensure that our existing sectors are shown the same attention and encouragement to reduce their energy consumption if we are to reach the net zero target; and pumps can play a significant role in this.